Nestled in the remote mountainside forests of Rishikesh in northern India, the Tiny Farm Fort stands as a testament to nature’s creativity and the power of community. Acknowledging the rapid decline in a centuries long tradition of using natural materials, architect brothers Raghav and Ansh Kumar formed the Tiny Farm Lab with the mission to challenge a homogenous future dominated by fired red bricks, concrete and steel. The result is a Tiny Farm Fort; a small curvaceous cob house with a deep connection to nature.

ARCHITEXTURES Editor-at-large Vanessa Norwood spoke to Raghav Kumar about his ethos of building through care, community and conscious materials, all powered by a serious amount of dancing!

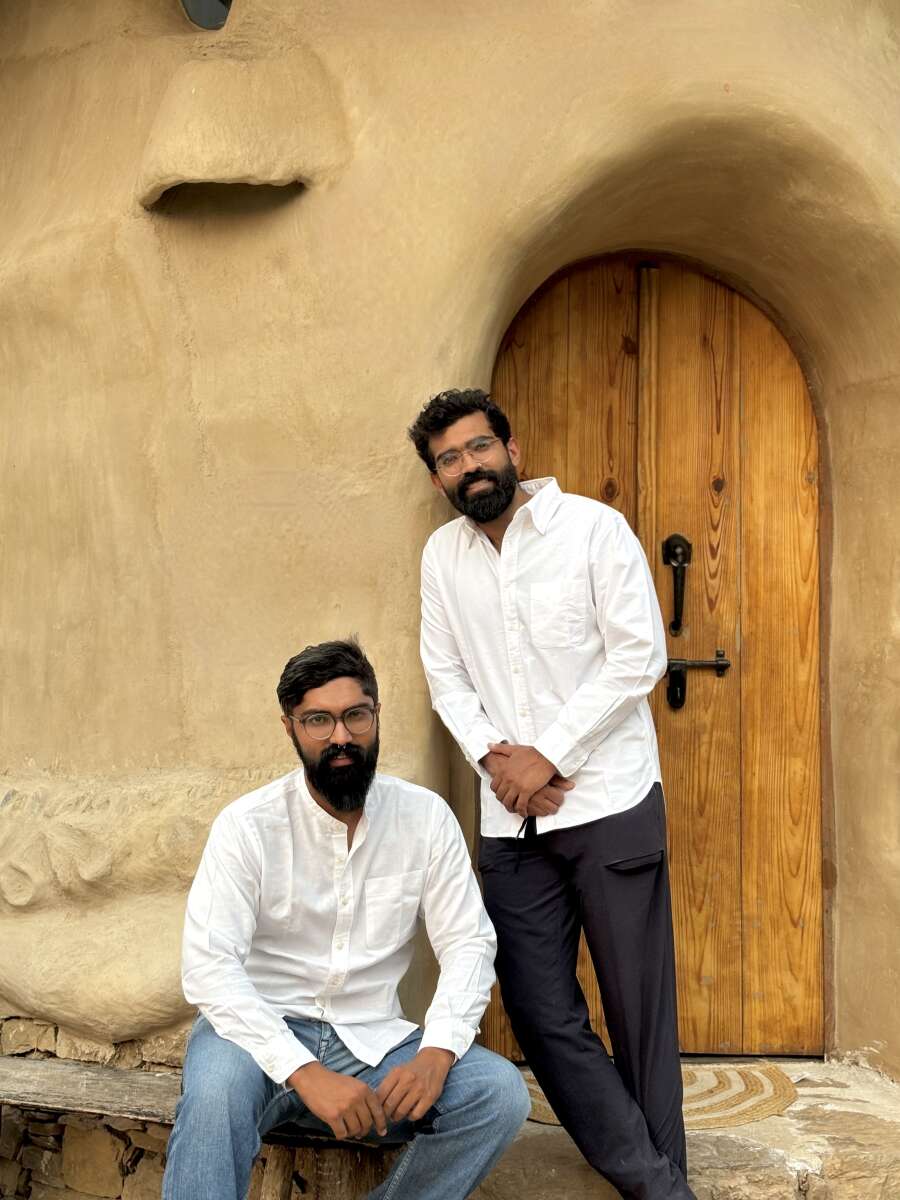

Left: brothers Raghav and Ansh Kumar. Image credit, Aishwarya Lakhani. Right: Close up view of the Tiny Farm Fort. Image credit, Atik Bheda

Left: brothers Raghav and Ansh Kumar. Image credit, Aishwarya Lakhani. Right: Close up view of the Tiny Farm Fort. Image credit, Atik Bheda

Vanessa: You went from four years of working in corporate architecture for a German company in India to living in a remote mountain village in northern India. What brought about such a radical move and how did you come up with the idea to make the Tiny Farm Fort?

Raghav: I quit my job when my hair turned grey! I was building a platinum rated green building that ticked all the point systems but deep in my heart I knew that this architecture was not sustainable. In the rating systems it stated that you must leave windows open for one week to let the toxins wash out. So why are we building with them in the first place? There is also a disconnect to labour – you are sitting in an air-conditioned office, and the labourer is working hard doing two or three shifts in the sun and you don’t know how the materials work. You’re working backwards; designing the facade and choosing the materials later rather than working with the materials to see what is possible.

I realised our built environments are very ugly now and have lost a sense of identity and belonging. I think fashion and architecture have been moving in this direction together. You could be anywhere in the world and wake up in a hotel room and it could be New York, New Delhi or London. Every building is the same.

I went on a natural building course and got to see what was possible and that was where I fell in love with cob. There’s a limit to what you can learn in a workshop setting and the idea was to build something from scratch. My brother and I quit city life and moved to the mountains to take up this self-initiated project to locate something with soul and community. It was a quest of truth and beauty; how we can create spaces that feel beautiful to everyone. That was the inspiration.

Side view of the Tiny Farm Fort. Image credit, Atik Bheda

Side view of the Tiny Farm Fort. Image credit, Atik Bheda

Vanessa: How did you set about designing a house that was in opposition to mainstream architecture and education?

Raghav: It was a departure from the traditional way of designing by first sitting at a desk on AutoCAD. The site was small and moving to the mountain countryside where we had to trek with groceries every day was a big lifestyle change. We took a lot of time to study the site, seeing how the sun moves, what happened to the water when the rain came, and asking what the land is trying to say. We used to lay down on the land to feel it. It was eight months before we started any construction. We wanted the house to look like it belonged there and grew out of the land. In response to the site, we finalised the foundation and doors openings and slowly started framing the views, noting where the light came inside. The aim of the house was to instil belief in people; you don’t need to be an architect. People came with no experience and within a day learnt how to build in cob.

Participants to the construction of the Tiny Fort Farm at work. Images credit, Hanish Bhateja

Participants to the construction of the Tiny Fort Farm at work. Images credit, Hanish Bhateja

Vanessa: You speak about reinstalling belief in bioregional materials – what research did you need to do to understand vernacular materials used in the area?

Raghav: The idea is to bring desirability to these materials, so that we are not just building one cottage, we can start slowly building in the suburbs, making them mainstream in the cities. One material is not the solution; we’re looking at a palette so that we can combine solutions that are not only economically viable but timeline viable.

Existing supply chains favour fired red bricks, cement and steel. Even in such a remote place the villagers are moving towards red brick construction, despite the red bricks needing to be taken on mules, but once the bricks are there the house goes faster and is seen as a symbol of progress, building something new.

Vernacular ways are just getting more and more difficult. Even though we live in a Sal Forest which is the strongest wood to build with, we can’t use any of the wood. Even the villagers can’t take wood. They used to take slates to build roofs, but this is now banned. I understand that we shouldn’t take all the materials from this remote forest to New Delhi, which is 250 kilometres away, but you can’t deny the indigenous population their own materials palette.

It is said that the local Sal tree (Shorea robusta) stands for a hundred years, falls for a hundred years and can survive another hundred years. As we couldn’t take trees from the forest we used eucalyptus beams, another hard wood, which has become the only option as there is no ban and it’s fast growing. They say it’s more termite resistant because it has its own eucalyptus oil inside. So, we had to get our timber from outside, even though we’re surrounded by beautiful trees. We also sourced some secondhand windows from the same nearby city and the waterproofing membrane. All other materials came from 50 to 150 metres from the site including the stone. We had to locate every rock by ourselves to excavate and break the stone foundations. To carry 40 or 50 Kgs of rocks even for 50 meters is a big challenge, especially on a rocky terrain.